Australia’s largest banks, such as Commonwealth Bank of Australia (ASX: CBA) and National Australia Bank Ltd. (ASX: NAB), have certainly had a tough run of late, with the ‘big four’ all down around 20%-odd from their one-year highs.

Of course, that’s probably not something a lot of long-term investors will lose sleep over. After all, the banks have delivered exceptional returns over the past couple of decades.

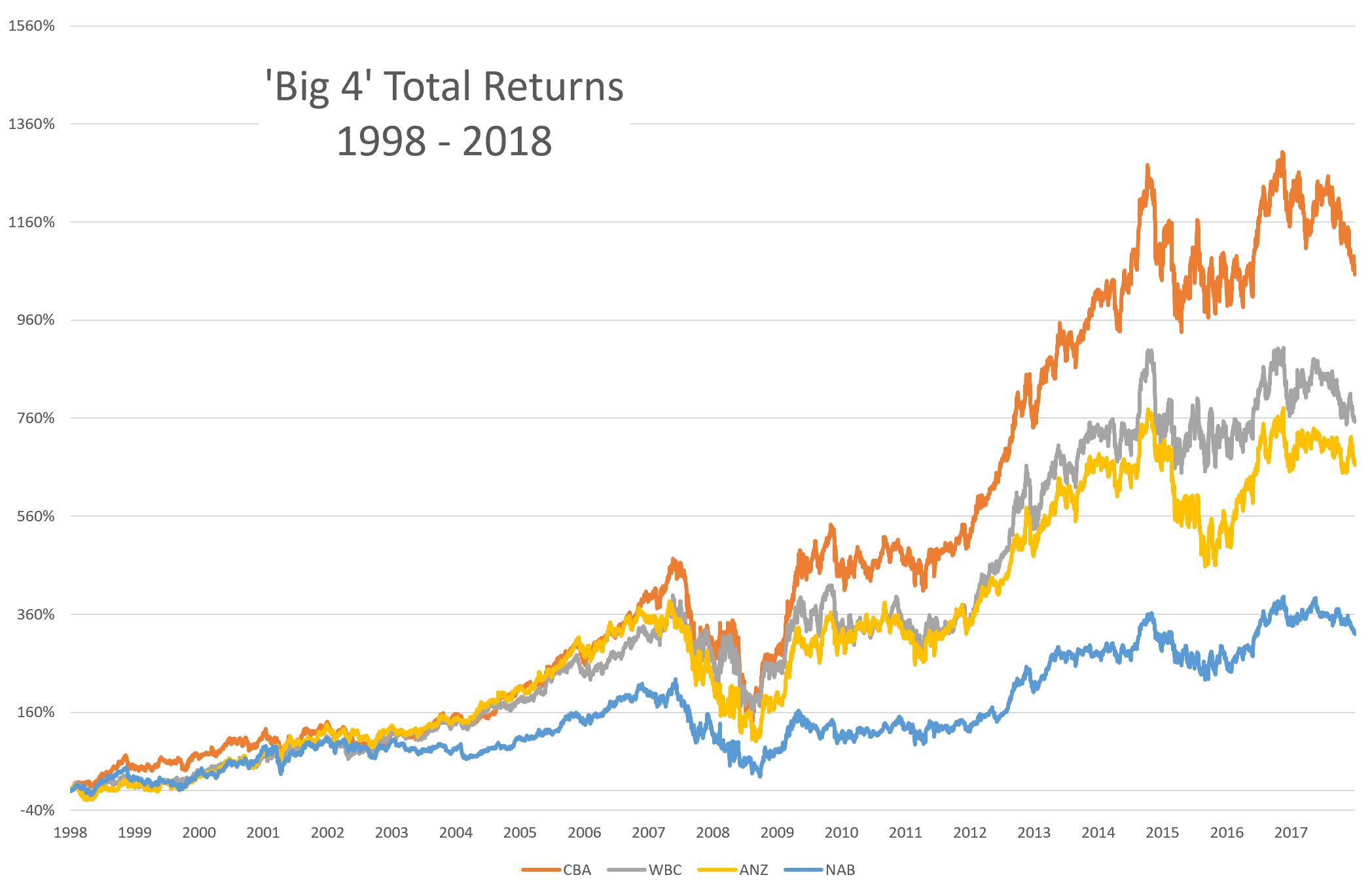

The Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) is a clear standout, generating a hefty 1,053% return since 1998 (including dividends). National Australia Bank Ltd. (NAB), on the other hand, which has been beset by offshore misadventure, has returned ‘only’ 319% — about 7.4% per annum (still enough to see investors more than quadruple their money).

But, that was then, and this is now. The real question for investors is whether they can expect that same kind of return to continue into the future. For a long time, I thought the answer was a firm ‘no’. But, with bank shares near multi-year lows, my perspective is starting to shift.

Is It Time To Buy ASX Bank Shares?

Before we get into valuations, let’s first examine the drivers of the banks’ historical returns.

At a high level, profit growth has been driven by a strong and enduring demand for the banks’ ‘product’ — that is, predominately, credit.

With Australia managing to avoid a recession for a record-breaking 26 years and enjoying a once in a century mining boom along the way, the economic landscape has been very favourable. And, when times are good, people tend to borrow more.

Added to that has been a number of ‘structural’ shifts. One that is little acknowledged is the shift to two income families. Since 1990, the increase in the female labour force has been close to double the rise for males (undoubtedly, a good thing). Today, households in which both Mum and Dad are employed represent around 60% of all couple households with children.

The reason why this is relevant is that it means that the income per household has increased substantially as a result — and the greater the household income, the greater the household borrowing capacity.

Another key factor fueling the demand for credit has been its falling cost. The lower the rate of interest, the more you can afford to borrow — and boy, has money become cheaper over the past few decades.

With Aussie households earning more and with debt becoming cheaper and cheaper, many of us went on a shopping binge. And the thing we desired most — by far — was good old bricks and mortar.

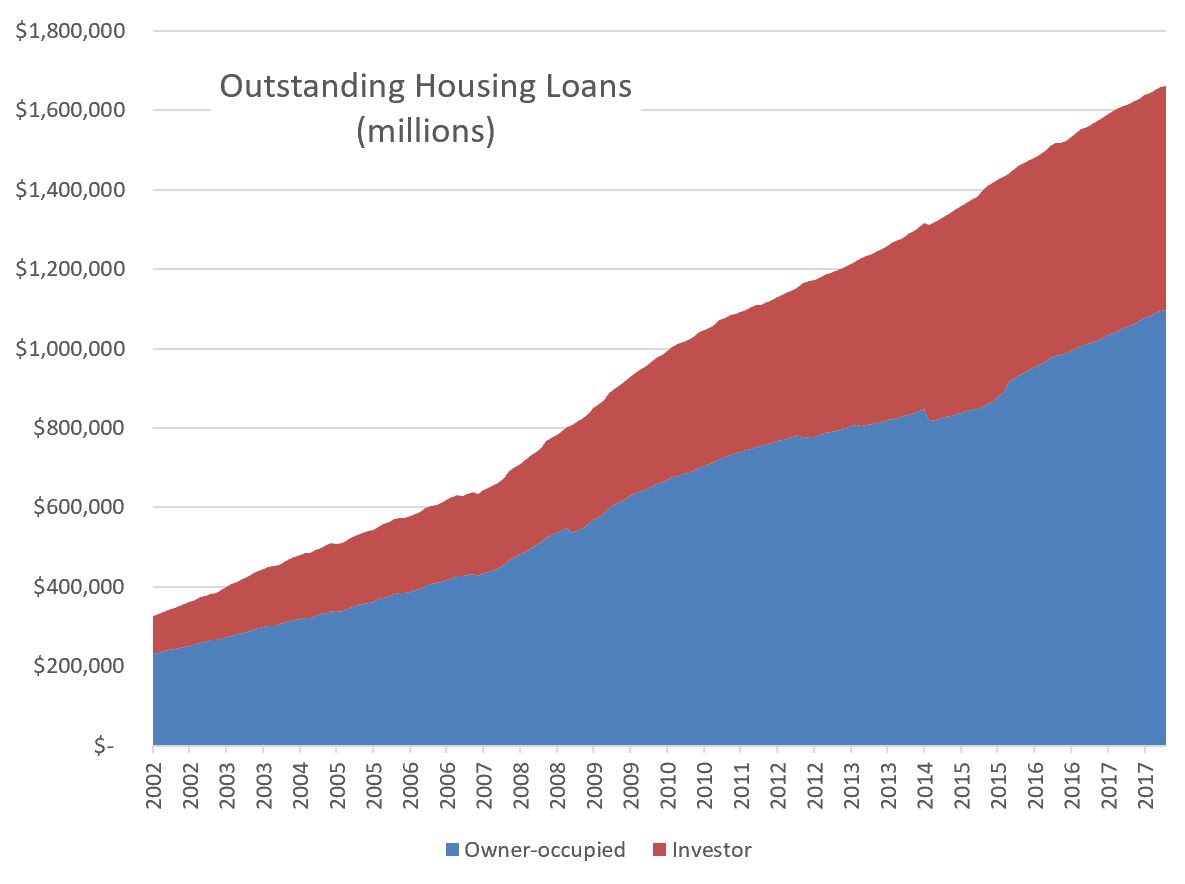

Since 2002, the level of outstanding housing loans in Australia has grown by more than 5-fold. On average, that’s about 10.7% annually, with growth in investment loans even stronger at nearly 12% per annum. That’s well above inflation or wages growth.

To date, much of that investment has proven worthwhile — especially in our capital cities, where prices have gone nuts over the past decade. Interestingly, those increased house prices have helped attract more investment in housing, as well as increase the equity of many households (the net worth of a property after accounting for debt), which itself has acted to increase borrowing capacity. Combined with other factors — such as tax incentives, and first home buyer grants — there has been a somewhat of a self-reinforcing loop.

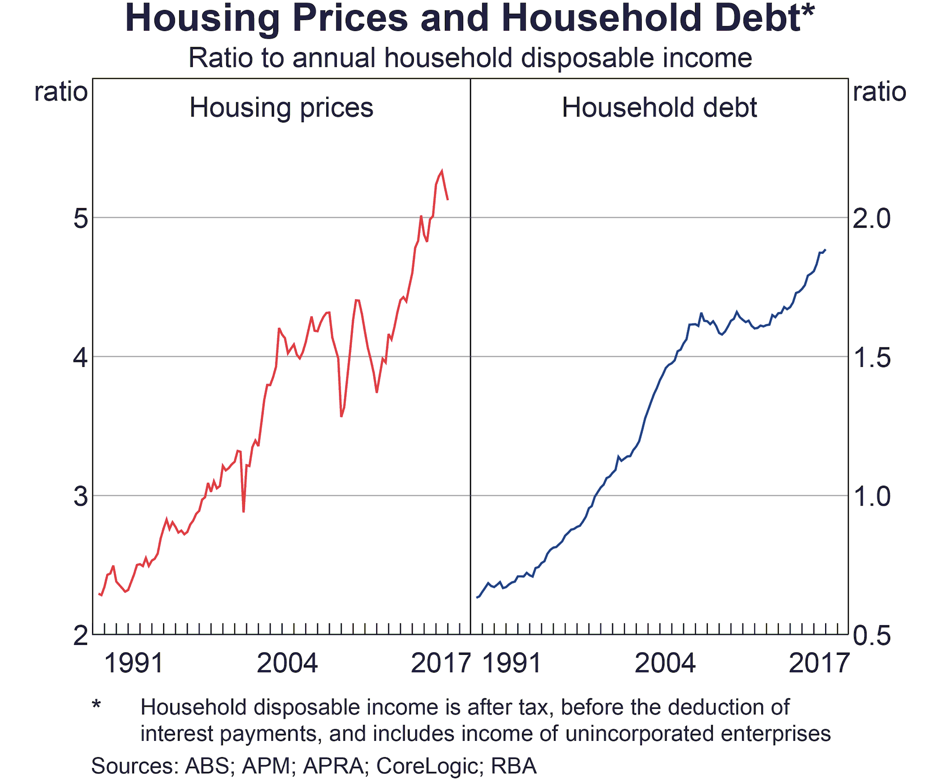

Our level of borrowing hasn’t just increased in absolute terms — but also relative to our incomes and assets. In other words, the average Aussie household has become much more leveraged. According to the ABS, the level of household debt has grown almost twice as much as household income since 1991.

The last big boost for bank profits has been the consolidation of the financial sector over time, especially since the GFC. The banks have strengthened their market power and branched out into a host of related financial services — not the least of which has been wealth management, which has been strongly driven by the wall of money provided by Australia’s compulsory superannuation scheme.

Is it any wonder the banks have done so well!?

But how likely is it that these phenomenal tailwinds will persist, at least at the same rate?

Incomes will no doubt continue to rise on average over the long term, but the pace of growth has certainly been lacklustre in recent times. Most economists see little hope of this materially improving anytime soon. Certainly, the structural shift to two-income families is a trick you can only pull off once — unless we plan to send the kids down the salt mine.

It is, of course, possible for interest rates to drop lower, but with the official cash rate at just 1.5%, there’s not a lot of room to move. Obviously, we can’t expect the approximate 16% decline in rates that we’ve seen since 1990.

House prices could well keep rising, but the rate of growth will likely be capped by affordability — and by most measures, we already have one of the most unaffordable housing markets in the world (a topic for another day, perhaps). Indeed, as has been widely reported, house prices have been on the wane lately.

Let’s not get distracted over the prospect for a housing market crash. Though that’s a possibility, what matters for this argument is simply that the pace of growth in house price, and associated credit, is unlikely to match that of yesteryear.

More broadly, without getting suckered into the folly of forecasting recessions, we should prudently expect one in the coming decade — if only because of the ‘law of averages’. It seems bold, to say the least, to assume that ‘the lucky country’ can avoid one forever. When that finally happens, we’ll be reminded of just how cyclical bank earnings tend to be.

Last but not least, the major banks are all looking to exit wealth management and other ‘verticals’, and a good thing too given what the Banking Royal Commission has uncovered. In fact, we can expect more stringent regulation going forward, which will no doubt limit bank profitability.

Let me be clear, I’m optimistic about Australia’s long-term prosperity. I’m certainly not trying to predict doom & gloom. But when it comes to identifying value, profit growth is key — and it seems almost certain that the big banks will, at best, achieve only low single-digit type earnings growth for the foreseeable future.

And, if the worst should happen (say, a housing downturn or economic recession), profits will likely take a big backward step.

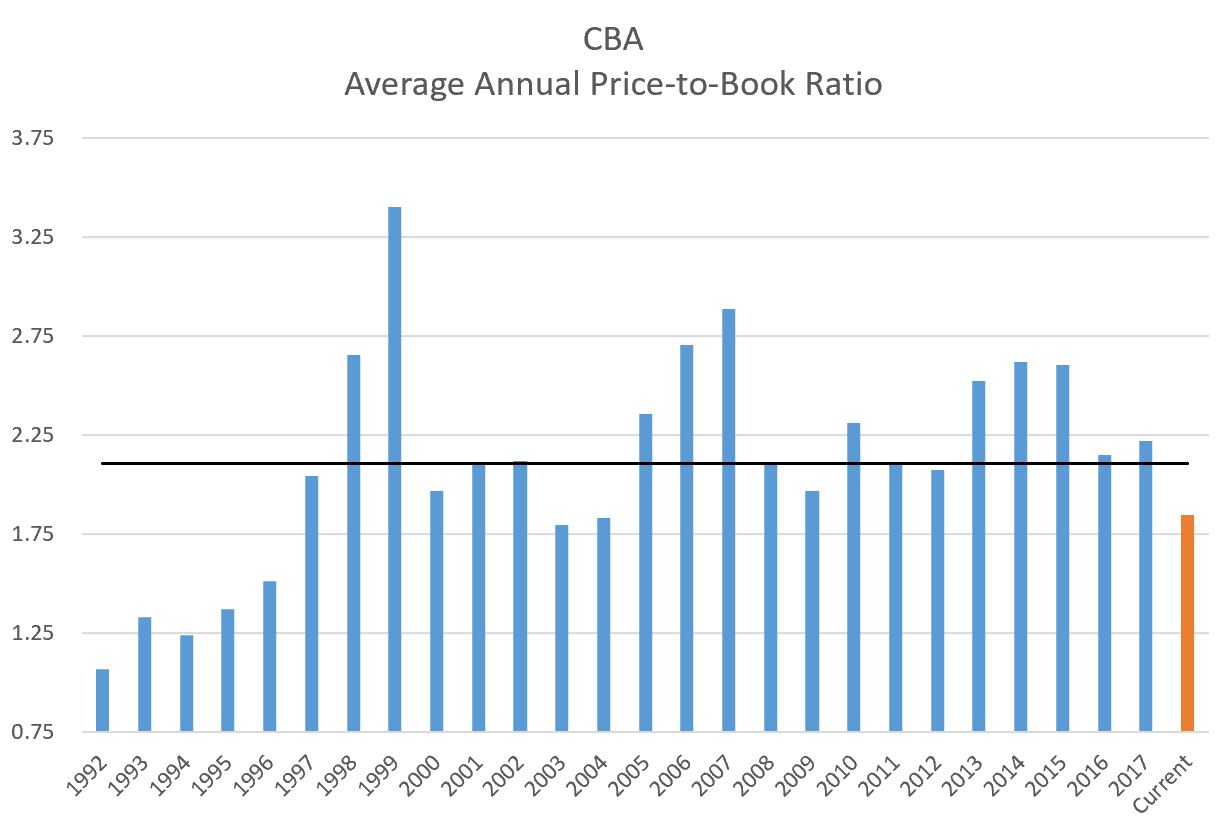

So there is significant asymmetry in the profit outlook for our major banks. That being said, for the first time in years, the market is starting to properly recognise this. Consider CBA’s price to book ratio, which (at the time of writing) is about the lowest it’s been in 14 years.

If we approach it from an income perspective, the value is also starting to become apparent. Sticking with CBA — which I consider to be the best of the bunch — we see that shares are presently offering a yield of 6.3%. When you factor in those lovely franking credits, you get a total income return of 9.1%. At this level, investors don’t really need much growth to do well.

Let me stress, though, I don’t think the banks are a bargain. A drop in book values or a reduction in dividends (yes, that can and does happen — just look at the GFC) could well undermine the attractiveness of the measures described above.

Nevertheless, I do think the banks are roughly around ‘fair value’. Long-term investors — especially those with an income focus — could do far worse than picking up some shares at current levels.

Needless to say, that doesn’t mean shares can’t or won’t fall lower still; the pendulum of value tends to overshoot on the upside and downside. And for those that would prefer a larger ‘margin of safety,’ it’s not unreasonable to demand a lower price.

Either way, for the first time in a long time, things are certainly starting to get interesting.

Like this bank analysis? If you want more free insights like this, I just launched a new investing website called Strawman. Best of all, it’s jam-packed with great investment analysis of ASX shares. Click here to join.

Get More Insights On Strawman – Australia’s Premier Investment Club

This article contains general financial advice or information only (under AFSL: 501 223) and should not be relied upon. This information does not take into consideration your needs, goals or objectives. Therefore, you should consult a licensed financial adviser before acting on any of the information presented here. Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. Andrew Page and Strawman hold no positions in any stocks mentioned.