What I’m about to say will rub some finance experts the wrong way.

How I’m Investing In 2019 & Beyond

When you’re deciding to invest you have a few options. They are:

- Via Super

- Managed funds

- Index funds

- With the help of a planner

- Robo advisers

- ETFs

- Individual shares, and

- Subscription Services

What I’m about to say could change the way many Australians think about investing and how they weigh up their options. Please read the entire article, even if you have to break it up.

Below, I’ll go through each of the above options one-by-one.

Superannuation

Super is the most ‘hands-off’ way to invest in Australia. Why? You couldn’t put your hands on it even if you wanted to because unless you’re over the prescribed age (~65) you can’t access your Super.

Right now the tax on Super makes it a decent choice for many Aussies on a good wicket but with changes every year it’s quickly becoming a far less desirable place to park your extra cash for the long run. This is especially true if you plan to retire with an amount of money that would make your life ‘comfortable’ — or better.

According to AFSA retirement standards, an Aussie couple currently needs to earn $61k per year from their nest egg to live a comfortable retirement. Just imagine how much money you will need to get $61k per year in passive income when interest rates are 1%.

I Bpay extra cash to my Super fund to cover insurance.

Managed Funds

For most people who do not have the time, inclination or temperament to invest in shares or bonds directly in their own name, a managed fund is what often comes to mind.

A managed fund is a fund or pool of money that’s managed by a professional. When someone says “managed fund” they’ll most likely be talking about actively managed funds opposed to ‘passive index funds’ (I explain the difference here).

The problem for most Australians is ‘which fund should I choose?’ There are thousands of managed funds globally and here in Australia we probably have more than our fair share.

To make matters lots worse, data sources like SPIVA tell us that ~79% of active fund managers would likely have done worse than extremely low-cost index funds or market averages such as the ASX 200. Keep in mind this is just five years of data.

It’s at this point that most investors will think to themselves ‘if active fund managers do so poorly maybe I’ll just buy an index fund?’ Keep reading…

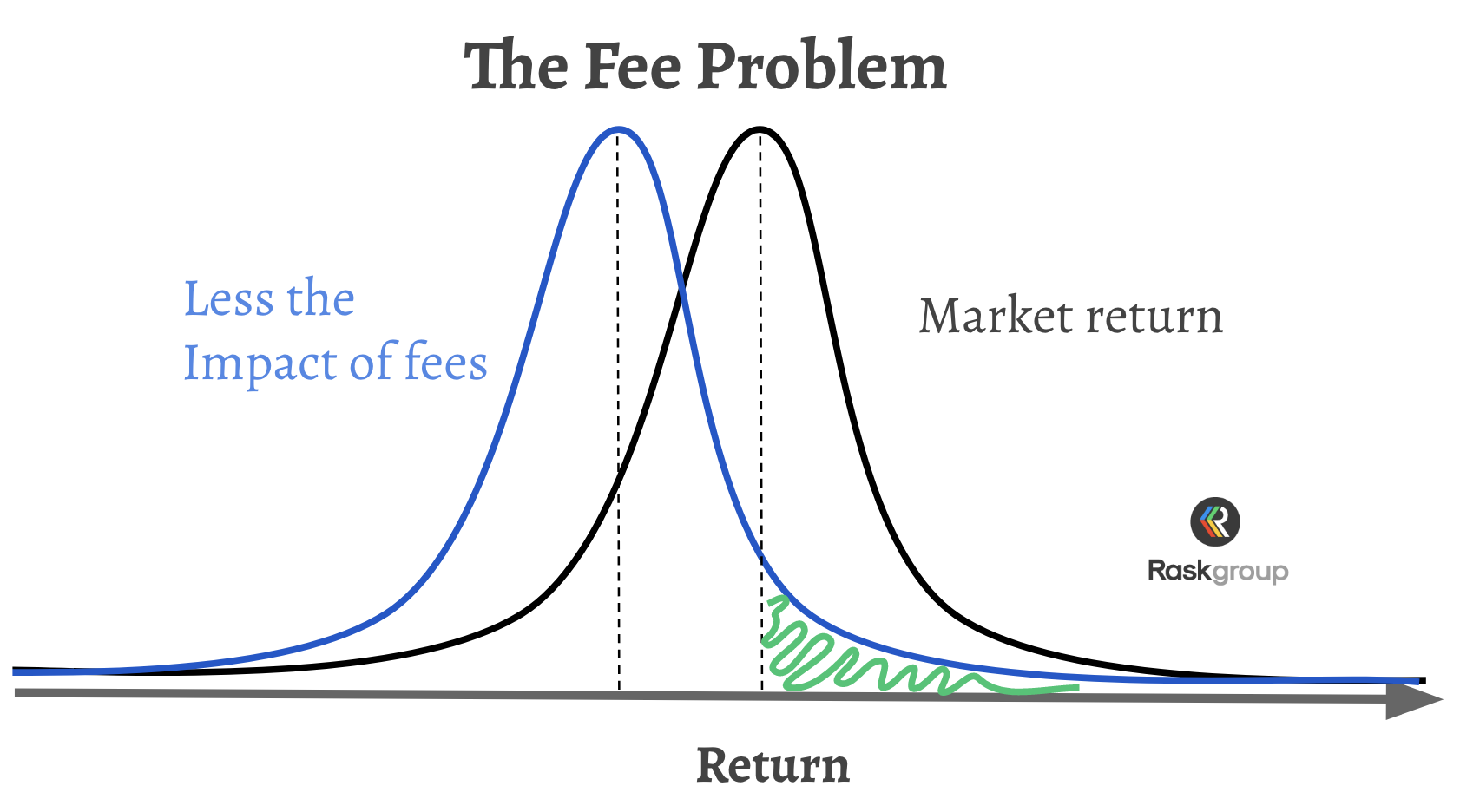

A big reason more than 50% of active fund managers underperform over the long-term is fees. If you think about it, most investors will perform around ‘average’ — the market return. This can be shown in a normal distribution.

However, with extra fees paid/incurred by fund investors each year, the normal distribution is effectively moved against the fund investor. Here’s a chart that gets tossed around a lot:

As you can see, it wouldn’t be good enough for a fee-earning active fund manager to do just average, they’d have to achieve the market average return + their yearly fees just to get back to breakeven for their investors.

There are other reasons why it’s hard for active fund managers to outperform. For example, they face pressure from clients, they deal with applications/redemptions, they often have to be fully invested, etc..

Unfortunately for fund investors not only is it hard — not impossible, but hard — to pick a star fund manager, an issue that often goes unnoticed is a hugely important thing called TAX.

If you look at a managed fund research report (or just your tax statement) you might notice this thing called ‘turnover’. This is a measure of the buying and selling inside a fund’s portfolio. Turnover is routinely high for fund managers who are very active or trade lots of stocks.

Who cares about turnover?

Turnover produces tax consequences for fund investors because they are the beneficial owners of what’s inside the portfolio. The thing is, you won’t see the impact of taxes showing up in a performance table, as much as some fund managers argue for it.

The broad market, low-cost index funds (see below) also have turnover but it’s often not as onerous for end investors because they’re not as ‘active’.

Managed funds can work very well for investors. Just imagine buying into a fund run by Magellan Financial Group (ASX: MFG) or Platinum Investment Management Ltd (ASX: PTM) when they first started. However, with high fees, tax implications and other issues, you need to tread very carefully.

Note: If you’re worried about fees you should know some good Australian fund managers will offer their services for zero base management fee (meaning they’ll only earn fees with good performance). However, they are a rare breed.

Index Funds

Index funds are a type of managed fund but they follow an index like the ASX 200 (for shares) or the Global Aggregate Bond Index (for bonds).

Day-to-day these funds are mostly run by computers using specific rules to include shares, bonds or whatever the index tracks. The costs associated with index funds are often — but not always — very low. Indeed, the best thing about these strategies is their low fees/costs.

In the sharemarket, index funds have tended to outperform active funds over very long periods because they have low fees and benefit from the ongoing growth in profits and dividends received from shares in companies.

There have been attempts by fund managers to improve the performance of traditional index funds. This trend has given birth to a wave of new strategies called ‘smart beta’, ‘rules-based’ or ‘factor funds’. While these strategies can be used effectively they can more easily be a failure. Most of them will likely prove to be a waste of time and money if you ask me.

Outside of shares, index funds can be a mixed bag. For example, in bonds, the most popular broad market index funds often use the ‘total debt’ of companies to decide which bonds to buy (i.e. the companies with the most debt get the biggest weightings — you can see why this is risky). Put simply, bond market index funds and ETFs tend to work — just not as well as their sharemarket brethren.

Ultimately, I think low-cost index funds are a good option for most people — but they’re not perfect. For example, share market index funds are prone to excesses in the market like steep overvaluation and deep undervaluation, and they buy shares of companies you probably wouldn’t want to support (unethical companies, poorly performing companies, etc.).

Again, low-cost index funds from the likes of Vanguard and iShares is probably the best option for many people but if you want better performance you’ll need to try something else (keep reading).

Advisers

Financial planners and advisers who offer a flat rate of fees and don’t take commissions can do incredible things for Aussie families and individuals. They can help you sort your budget, insurance, Super, taxes and where your money is invested.

However, they should know what their core competency is — or is not. For example, if they are ‘dabbling’ in stocks I’d go elsewhere for my advice and research (see below).

The thing that gets me is most Aussies have very simple financial lives (PAYG, a house and shares) so they don’t need a financial adviser to oversee their finances permanently.

Leading up to retirement or in ‘special situations’ advisers are important professionals (e.g. for estate planning matters, inheritances, the passing of a family member, etc.). However, once you have a decent budget that works for you, your Super is sorted, you’ve got the right insurances and you’ve started learning about investing — just do it yourself!

I started the Rask websites, podcasts and brands (specifically Rask Invest) to educate people to DIY their finances and invest better because I believe the ONLY way to empower yourself — and get the best returns from your money — is to do it yourself!

Just like an adviser/planner you’ll make mistakes if you go it alone. However, once your finances are flying on autopilot, and you’re investing, you can come to terms with the mistakes you make and begin to back yourself to know what’s right for you.

I believe that if Aussies can commit a small amount of time, even 15 minutes per day or 30 minutes per week, to learning about finance and investing they can learn 99% of the important concepts after a few years. That knowledge will then snowball over your lifetime and can lead to far better outcomes.

(insert shameless plug)

We created the first 10 episodes of The Australian Finance Podcast to offer an overview of everything an Aussie single or family would want to know about finance and investing.

Bottom line, a great financial planner can help you plan your finances and strategy but don’t let him or her run it for you. It might save you bucketloads in fees and you’ll be more confident if you just do it yourself.

ETFs

Exchange-Traded Funds or ETFs are the same things as managed funds, rules-based or index funds. The only major difference between a managed fund and an ETF is that an ETF can be bought and sold on the sharemarket using your share brokerage account.

Indeed, don’t be fooled into thinking ETFs are always the same thing as index funds (even some experts still don’t know this!). Only some ETFs use index strategies. For example, some ETFs are actually actively managed funds or invest in commodities like gold or hold bonds or currencies.

I often describe ETFs as the ‘wrapper’ around a strategy/fund. It’s what’s inside that counts.

Robo Advisers

Contrary to the image that just popped into your head when you read ‘Robo advisers’, these things are not run by robots in server rooms or dark offices tapping on a keyboard. Right now, Robo advisers simply use rules to recommend a portfolio for a user/client.

Here’s how simple it could be:

Website: “Hello User X, tell me, would you panic if your shares fell 30% in one year?”

You: “Yikes, absolutely I would!”

Website: “Well then, we recommend you use a low-risk investment option. Click here to sign up.”

Robo advisers typically invest in a diversified portfolio of index funds or ETFs on your behalf.

You read that correctly.

Robo advisers simply invest your money in the index funds or ETFs that you could buy in your own name. But thanks to the wonder of technology, robo advisers can provide tax reporting software, track your performance and allow you to add more money regularly with a payment plan. In exchange, the robo adviser will take a percentage fee.

Here’s the rub (and a secret Rask tip): if you care about fees and want something simple but effective: why not just buy a diversified ETF from the likes of Vanguard?

For example, the Vanguard Diversified High Growth Index Fund ETF (ASX: VDHG) has a management fee of just 0.27% per year and invests across Australian shares, international shares, local and global bonds automatically. One investment, one tax statement, diversified exposure. Very low cost. What more could a passive investor want?

To be clear, I’m not saying it’s right for everyone and there are risks to any investment — always read the Product Disclosure Statement of a fund or ETF before you buy in — but you get my point. Why not just buy an index fund?

Individual Shares

Finally, we get to buying and selling individual shares/stocks. This is my favourite way to invest but please note that I’m biased because my business makes money from investing research.

Individual shares can be bought and sold the same way as an ETF. That is, you set-up a share brokerage account (free), fund it and then you’re ready to rock and roll a couple of days later.

There are many reasons why I choose to invest most of my money in individual shares so I’ll try to be as concise as I can be and list them here:

- Costs. Brokerage is the fee to buy and sell shares. Fortunately, is reasonably low here in Australia and starts about $10 per buy or sell. If you invest $100k a pop it might cost a bit more like 0.12% of the trade value. The important thing to note here is that the brokerage fee is a once-off cost. Most good online brokerage accounts do not charge account fees or a yearly management fee. For example, if you have a $100k share portfolio with 10 or 20 shares it might cost you up to $400 ($20 per order) to buy the shares and get started. If you decide to invest $2,000 extra per month it might cost you another $240 per year. But here’s the thing: once you own your stocks you own them. If they perform well and their value goes to $150k, for example, it doesn’t cost you any more just because they have gone up. That’s because there are no yearly management fees applied to the value of a typical share brokerage account (of course, read the T&C’s because each account will have different fees).

- Learning. Shares are part ownership of businesses — find out what they are doing before buying. I research companies to buy and hold for (I hope) many years. Unravelling what exactly it is that a company does and plans to do is great fun and probably the highlight of share investing.

- Tax. If you like to invest as I do — find great companies and hold them — the taxes associated with your investing should be very minimal year to year. For example, last tax year I sold two stocks and I bought about 5-10. That’s not a lot. And of course in years from now if I decide to sell my best-performing shares I’ll likely have to pay tax (as I should). But in the meantime, I can try to compound like there’s no tomorrow knowing that tax rules favour long-term share market investors in more ways than one.

- Access. You could probably check the balance of your brokerage account every second of every day if you want to. Also, you don’t have to wait until age 65 to access your funds if you decide you need to boost your cash levels.

- Timeframe. Most professional investors are hamstrung by rules, mandates, window dressing or a myriad of other things that keep them from investing how they would if it were their own account. As the captain of my own investment portfolio, I can hold onto shares in a great company for as long as I like. I don’t have to please anyone other than myself (and my other half, of course!). I’ve found that the best investments in the sharemarket tend to take years to pay off. Not days, weeks or months but years. It’s often the case that professional investors can’t wait that long because their clients will get impatient and pull the rug from under them.

- Alignment. Who’s looking out for you? Answer: you are.

No-one will be impacted more by your investment performance than you are. As the controller of your own investment portfolio, you’ll make plenty of mistakes. But I’m confident in saying that you’ll learn from your share investing mistakes because they were yours to make. You’ll also learn from your winners because you made those too. If someone else makes them for you, it’ll be the wrong lesson that’s learnt. - Superior performance. Many major index fund providers publish a 10-year ‘investment outlook’ report once per year. In the past year, the outlook statements from the major index fund providers had a grim tone because their experts are currently predicting yearly investment returns ranging from 4-8% over the next decade. I don’t know about you but 4-8% per year doesn’t exactly get my pulse racing. The outlook range is well below even the historical average yearly return of sharemarkets which tended to be between 8% and 12% depending on which market you’re looking at (Australia, US or global) and the timeframe you use.

What’s important to note, I think, is that the best companies on the sharemarket will continue to grow their operations much faster than others for many years to come. I believe the best companies — those that are well-led, defensive, growing and competitively advantaged — will produce returns on their invested capital (ROIC) well over 20% per year. That’s not to say shareholders will capture all of that 20% return. But you need only look at stocks like ARB Corp (ASX: ARB), TPG Telecom (ASX: TPM), Fortescue (ASX: FMG) or even Google (NASDAQ: GOOGL) and Facebook (NASDAQ: FB) (both companies I own) to see what a good business can do for its shareholders. No-one will pick every winner but if you get a well-priced basket of 20-30 great companies in your portfolio I reckon the odds of superior tax-adjusted long-term outperformance is stacked well in your favour.

Subscription Services

Finally, I’m going to add Subscription Services to my list of ways to invest. These research and information services often go unnoticed in studies but I run one so I’d like to think I know a thing or two about them.

These services offer research (e.g. share ideas) produced by investors who should have the time, inclination, education and temperament that’s suited for investing.

Basically, an Aussie investor working 9-5 can use these types of research services as a shortcut to finding great shares to buy and ETFs or funds to invest in.

When you’re weighing up which Subscription Service to go with, consider the following:

- Is the investment adviser aligned? If you get your investment research from an analyst or adviser who doesn’t buy the shares they recommend you’ve got to ask yourself why. Important point: they should be required to buy the shares after you/their members get the opportunity to buy first. If the stock idea is that good they won’t need to front-run their members or buy it immediately after the research is released.

- How many stocks do they recommend? If you’ve invested before you’ll know that keeping up with 20 stocks is hard enough — let alone 50. If the adviser or analyst provides coverage of 50 stocks and they don’t buy them they’re probably just licking their finger to see which way the wind is blowing.

- How often do they make a stock pick? Patience doesn’t lose you money. Much like when a great fund manager must remain fully invested when they know markets are expensive, if an investment adviser is forced to pick a share every week or month it can erode the quality of his or her research. Do you want their best ideas or just a new one?

- Transparency. If your adviser makes a mistake do they try to cover it up, explain it away or do they own it, learn from it and keep it against their track record?

- Don’t forget the fees. Research services and investing newsletters usually cost a few hundred dollars per year. The cheapest ones are often the most expensive because the quality of the research and engagement from analysts is low. The most expensive newsletters (I’ve seen some charging $5,000 plus) aren’t always what they crack up to be either.

What Now?

Now that you know what your options are and what to look for, I want to make one thing very clear: you don’t have to choose one way to invest. For example, I invest mostly in direct shares for Rask Invest but I also own rules-based ETFs and index funds. And in time, once the Rask Invest model portfolio gets large enough, I’ll start to research and invest with active fund managers who have their funds listed on the ASX. Like most Aussies, I also have Super.

Knowing what’s right for you isn’t an easy decision to make but I hope this article cleared some things up. I wish you all the best with your investing.

***

[ls_content_block id=”19823″ para=”paragraphs”]

Disclosure: Of the companies, products or services mentioned, Owen owns shares of Alphabet/Google and Facebook and he runs Rask Invest, a members-only platform which provides share and ETF research and more.