Maven Funds Management’s Matt Joass, CFA, takes us through the hidden and wonderful world of ASX-listed small-cap shares.

Hidden within the ASX is a beautifully inefficient market. It’s weird, under-researched, and entirely off the radar of most fund managers. That’s great news for those of us eager to do the work. It means saying no to a lot of companies. Thousands of companies in fact. But that process of elimination leads us to a precious few companies with very attractive underlying economics.

Of the roughly 2,200 publicly listed companies in Australia, approximately 70% of them (or over 1,350 companies) are not included in the ASX All Ordinaries Index. These businesses may be small individually, but they are numerous. Collectively they represent a total market capitalisation of over $80 billion with revenues of over $50 billion. The list includes some large international businesses that have chosen to dual-list in Australia, but for the most part it is hundreds of smaller companies.

Some of these businesses are bizarre. Most of them are terrible. But a precious few are diamonds in the rough. As I wrote in How to Catch a Monster, the greatest market-thumping success stories typically started out small. Our job is to find them.

Turn those rocks

Peter Lynch is one of my all-time favourite investors. Over the 13 years that he ran the Magellan Fund at Fidelity Investments, Lynch generated a 29.2% annual return. That return was more than double the market’s and made Lynch one of the greatest fund managers of all time.

Lynch’s philosophy of expansive research has been hugely influential to our approach at Maven Funds Management. Lynch describes this process as turning over rocks, searching for the hidden gems hiding beneath. Most rocks will turn up nothing, but the more that you flip over, the better your chance of finding a diamond in the rough.

“The person that turns over the most rocks wins the game. And that’s always been my philosophy.” – Peter Lynch

Our process

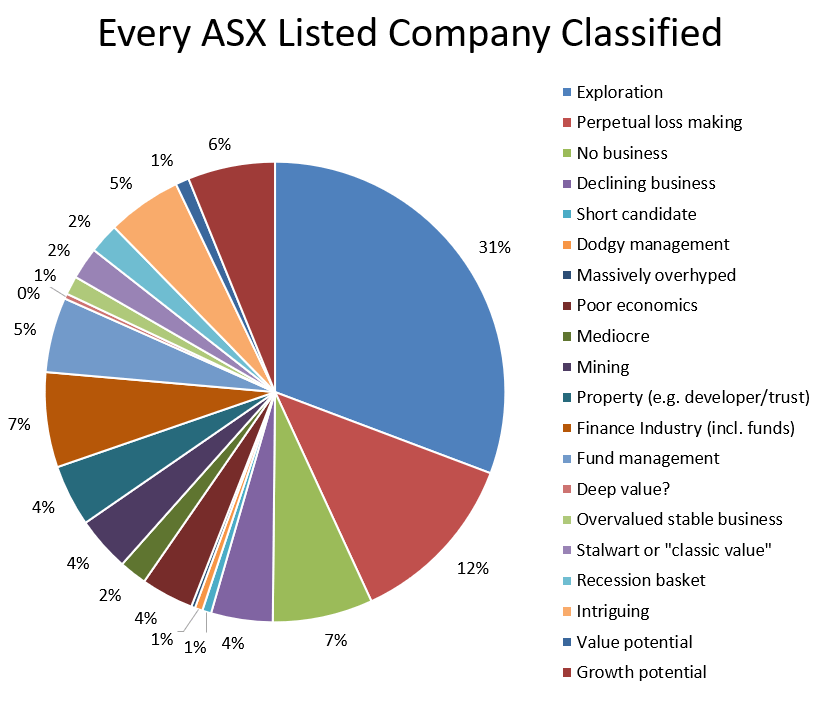

We went through and categorised each of the 2,200 businesses listed on the ASX into one of 20 categories. We did this by hand, one by one. Automated screeners have their place in investing, but it’s hard to replicate a human’s ability to recognise patterns and anomalies, then classify them appropriately. It takes longer, but it’s worth it. Going through thousands of companies individually also helps to train our brain’s pattern recognition system, to identify the few truly exceptional companies, and isolate what makes them stand out.

Without further ado, here are the results of our analysis:

The ASX is dominated by some terrible businesses. The first thing that jumps out is that ‘thrill and drill’ speculative mining explorers alone make up almost a third of all listed companies.

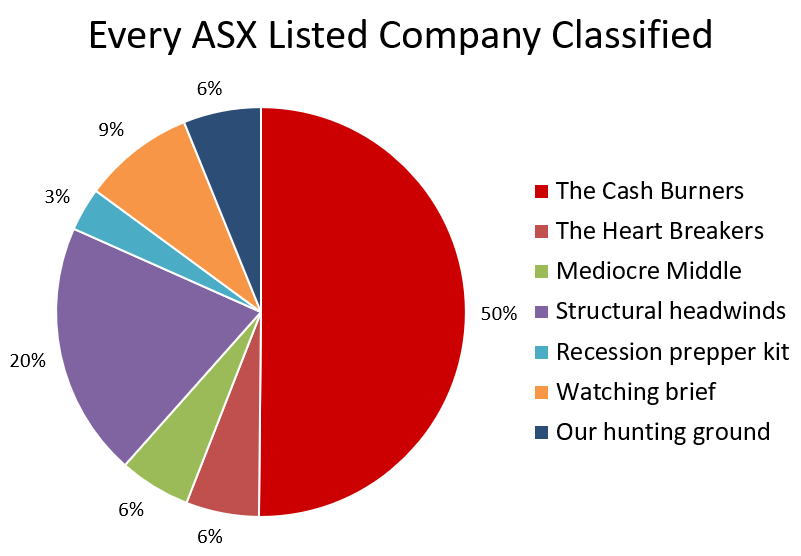

Beyond that initial observation, it’s helpful to consolidate things further. We identify seven broad groups.

#1: The Cash Burners

If these businesses were a Christmas present, they’d be a lump of coal. If that lump of coal also kept asking you to give it more money every six months. Not for us.

There are three groups that we have included in this group: speculative mining explorers, perpetual loss makers, and the mysterious ‘no business’.

When we say mining explorers we aren’t talking about mining companies that have meaningful revenues and also do exploration – we separated those out into their own group. No, these are the speculative explorers that, as a group, destroy shareholder capital. They repeatedly raise rounds of funding, and dilute shareholders, in the hopes of one day striking oil/gold/uranium etc. Every now and then a few of them do, and provide just enough hope to keep the whole party swinging

The perpetual loss makers require some judgement. When we come across a company that has a history of losing money, we need to determine if it’s temporary, or structural. Is the business aggressively investing for growth (potentially a good thing), or is it a money pit with terrible economics (a very bad thing). Unfortunately in our view there are hundreds of businesses that fall into this perpetual loss-making camp on the ASX. A large chunk of these are bio-techs, which are just as speculative as the mining explorers, but perhaps with a little more social purpose.

The ‘no business’ group are companies that have effectively ceased operations. And yet they somehow live on, trudging through the world as zombie shell companies. Typically these are failed mining companies, or biotechs, drifting towards the abyss of bankruptcy. Every now and then a new company that wants to list will come along, inject itself into the zombie, take over it’s decaying crust, and emerge as a shiny new business. Well at least newish. Often the leftovers of a failed mining company will hang around as the new business is talking up it’s amazing breakthrough biotech prospects. But that’s a story for another day.

If you simply avoid the 50% of ASX businesses that fall into this cash burner category, you will probably do quite well.

We avoid these cash burners like the plague.

#2: The HeartBreakers

If these businesses were a fiance, they would break up with you via a text message. These businesses are the tricks for new players. The value traps, and the overhyped flops. They’re heart breakers, and a great person like you was always way too good for them anyway.

The biggest component of this group are declining businesses. These companies are in a state of decay, each year worse than the last. These companies trade at low multiples, which attracts some bargain hunting investors. Some investors can make these declining businesses work for them, but for the most part they are ‘value traps’: cheap investments that are forever becoming cheaper.

Also included in this group are the massively overpriced companies that are at the top of a hype cycle. A few may even be compelling short candidates. Sprinkle in some dodgy management teams and you have the perfect recipe for a heartbreak cocktail. Steer clear.

#3: The Mediocre Middle

If these businesses were a seat on an airplane, you know which one they would be. I’m told that some small group of people prefer the middle seat. These people are odd, and should be treated with suspicion. For the rest of us, the mediocre middle are companies to be avoided.

These businesses are not terrible, but they’re not great either. Outside of the weird market that is the ASX, most businesses in the world fall into this category. They don’t generate great returns on invested capital, or attractive profit margins, but they do just well enough to keep the lights on. Business is tough, and these companies are battling for every cent.

It can be tempting to add these businesses to your portfolio to get some diversification. Or just because it’s hard remaining patient until you find great ideas. But hold your nerve, we’re almost there.

#4: Structural Headwinds

These businesses are in a similar boat to the group above. They typically have mediocre returns on capital across the economic cycle, or other structural weaknesses. But it’s not really their fault, it’s their industry.

When it comes to building and holding competitive advantages, certain industries are structurally weak. Airlines are a great example. It’s a capital intensive industry, and those assets can be quickly relocated at the first whiff of a competitor’s profit. Like a pack of hungry seagulls smelling a hot chip, the competing airlines swoop in, and the profits disappear. That’s great news for consumers, but bad luck for investors like us.

Other industries we avoid include: miners, because they are dependent on the vagaries of commodity market swings; property developers, due to their boom-bust economics, and banks, due to their significant exposure to an over-indebted consumer.

These businesses are highly cyclical, and in many cases operate at the whim of regulators. There is a time in each economic cycle where these companies can be quite attractive, and we would consider some of these at the right time, but that time is not now. Playing the cyclical merry-go-round isn’t our ideal game either. We’d much prefer to hold out for companies that we expect to be able to continue growing throughout all (or at least most) economic environments.

#5: Recession prepper kit

Most of our process is knowing which companies to avoid. So far in the previous categories we have already set aside 82% of all ASX listed companies. Don’t your shoulders feel a little lighter just thinking about that? This is where it starts getting fun.

The Discovery Channel show Doomsday Preppers chronicles American families that have started hoarding canned whole turkeys (yes that’s a thing), beans, gold, shotguns, etc, as they prepare for whatever variety of looming apocalypse they think is heading their way. Broadcasting your stash of food and supplies on international television is probably not the smartest survival strategy. But at least they’re thinking ahead.

There are 76 companies on the ASX that we’ve highlighted to return to if when a recession hits Australia. There are two types of businesses that we are interested in here. The first is high quality businesses with very stable and growing cash flows that are currently significantly overvalued. These businesses are too expensive for us to purchase right now, but times of great market panic bring great investing opportunities. When a recession hits, we’re ready to pounce.

The second type may seem counterintuitive. These are businesses that we think will be hit hard in the next recession, but where we expect the business to survive. These businesses should then bounce back strongly as fundamentals in the economy improve. In the meantime, we wait. As I wrote previously in ‘The Hidden Power of Inflection Points’ the time we’ll be looking to buy is when there is clear evidence that the recovery is already underway. A combination of temporarily depressed cash flows and multi-year low valuations can be a powerful way to see a stock surge.

In times of stress it is critical that we play offence and not defence. Keeping a ‘Recession prepper kit’ is a key component of that strategy.

#6: Watching brief

There are two main types of companies in this group. The first are those with potential as classic value investments. These are solid businesses with decent returns on invested capital. They often have a legacy competitive advantage that allows them to earn those returns. But they aren’t currently able to leverage that advantage into sustainable growth. We want to keep an eye on these businesses. As I wrote in ‘The Hidden Power of Inflection Points’ if these businesses are able to reignite their growth engine, and we can catch them early, we’ll be in an excellent position.

The second type included are those companies that we call ‘Intriguing’. They’re not good enough to make it into our hunting ground. Perhaps the fundamentals aren’t quite there yet. But there is something about them that we think is interesting enough to keep an eye on. Maybe it’s a unique product, or an emerging new market, or an unusual intangible asset. Whatever it is, we see some potential for this to one day become a great business. But we are also mindful that most ‘going to’ companies don’t end up going anywhere.

We keep an eye on these businesses, if we see signs that they are gaining traction, we’re ready to pounce.

#7: Our hunting ground

We’ve saved the best for last. These companies are the rare few we consider having the potential to be worthy of further research. This group of 136 companies represent just the top six percent of our investment universe.

These are high-quality businesses that demonstrate several of the following characteristics: fast growth, competent management, high returns on incremental invested capital, growing competitive advantages, rock-solid balance sheets, and attractive unit economics. Ideally these businesses will be tipping past a fundamental inflection point, and be trading at an attractive valuation. We’ve written a lot about these businesses previously. These are the type of companies that have the potential to be significant long-term winners.

The next step

This manual screening is just step one. What comes next is the real work of deep research. Ultimately, we want to filter down to the very best 1-2% of businesses in our investment universe.

It’s not easy saying no. It’s even harder to say no thousands of times. The process requires us to ruthlessly cast aside the pretenders that don’t measure up. But by doing so we give ourselves the best chance to identify those precious few Monsters that generate the vast bulk of the market’s total long-term returns.