What is quantitative easing?

A discussion with our Chairman, Ian Murdoch, suggested it would be worth offering readers an insight into what the term Quantitative Easing or QE actually means.

To start, quantitative easing forms part of the ‘monetary policy’ implemented by central banks around the world, including the Reserve Bank of Australia and the United States Federal Reserve.

The role of these institutions has traditionally been to focus on ‘price stability’ meaning to ensure inflation is neither falling or rising too quickly and to maintain an efficient banking and financial system. The latter objective being broad enough to effectively allow anything.

How does QE work?

The how of QE is quite simple: central banks use cash on their own balance sheets to purchase Government (and potentially other) bonds from recognised institutions like banks, pension funds and investment institutions. For some background, all banks and insurance companies across the globe are required to hold a certain amount of capital to support their lending activities, with Government bonds the main portion of this.

The cash can either be from the money they already have or alternatively, like in the case of Australia, the Reserve Bank may simply ‘create’ money out of thin air by adding say $5 billion to their digital accounts. So, the Reserve Bank is simultaneously increasing the size of their assets and liabilities (being the account of the seller) by the same $5 billion.

Another QE policy announced by the Reserve Bank in March was the provision of a $90 billion line of credit to banks.

Why do QE?

The aim of quantitative easing is ultimately twofold:

- To reduce interest rates for borrowers of all kinds, and

- To facilitate the faster flow of capital around the economy.

You see, every investment and loan in the world is priced off Government Bond or ‘Risk-Free’ interest rates. In the case of investments, Government bonds indicate the return investors receive for taking little to no risk and hence the base return requirement to invest in riskier assets.

The action of purchasing Government bonds en masse increases the value of these bonds but also reduces the yield they offer to investors like banks and pension funds, which ultimately forces them to look elsewhere with their capital.

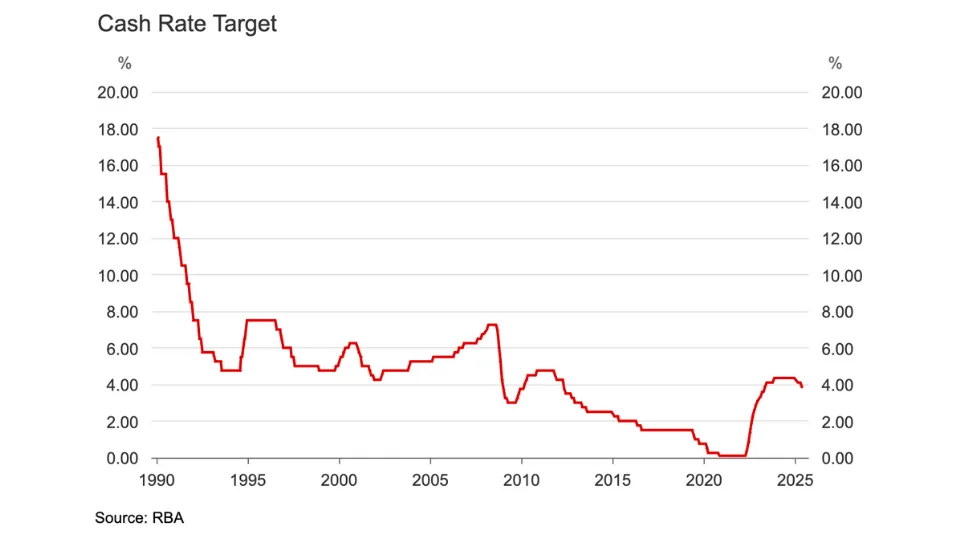

In the case of Australia, the Reserve Bank is specifically targeted an interest rate of 0.25% on three-year Government bonds. As you would expect, when interest rates are near 0% or negative in some cases, banks are disincentivised to leave funds in cash with the central bank for an extended period of time. Central banks hope this results in the influx of cash being deployed to offer new loans to businesses and consumers.

In the case of lowering interest rates, every type of loan in the world is also benchmarked against government bond rates. Residential mortgage rates are determined by setting a ‘risk margin’ above the prevailing bond rate to ensure the bank is being rewarded for any additional risk. This includes the bonds issued by the banks themselves to raise capital to lend to their own customers.

Importantly, these bond rates are not only the ‘cash rate’ announced by the central bank, but the daily traded bonds of all maturities from one to 30 years. Intuitively, by keeping the banks own cost of funding low (at 0.25%) and the returns on any excess capital near zero, banks are able to lend profitably and confidently.

How does it work in Australia?

Importantly, QE has at least five different stages, from QE 1 through to QE 5, with the Japanese one of the first to embark on the program in 2000.

Not only are the stages different but so is the implementation. In the case of Australia, the Reserve Bank has expressly stated that they will only be purchasing Government Bonds via the secondary market. That is, from existing owners and not directly from the Government itself, a very different and complex proposition.

In the case of Australia, the Reserve Bank has specifically indicated that it will purchase as many bonds as required to keep interest rates on three-year bonds at or below 0.25%. In addition, the Reserve Bank has also announced a $90 billion line of credit will be made available to the banking sector directly, secured by their own cash holdings, at a fixed rate of 0.25%.

Again, the aim is to fix a portion of the banks’ cost of capital at 0.25% and allow them to lend more at today’s ultra-low interest rates of ~2.5% whilst still remaining solvent. The last point here is the key:

If a bank lends at 2.5% but must pay 3.0% for that capital, they will simply not lend and the economy will contract.

Side note: How does QE relate to our Government spending?

One last side note. Many readers will likely be questioning where the $100 billion the Federal Government is spending will actually come from.

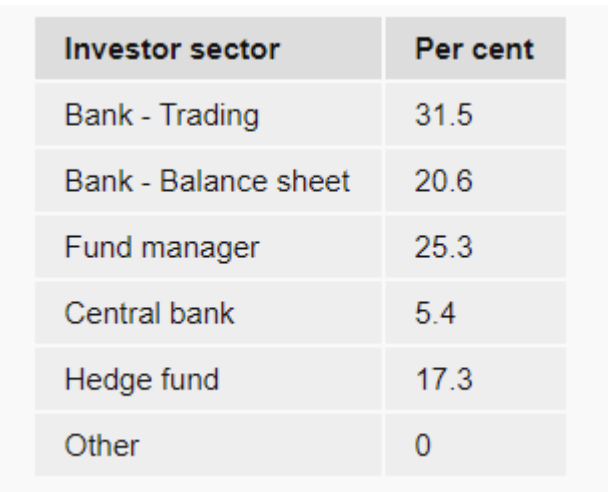

The Government funds its spending via a combination of tax revenues and bond issuance, with our debt-to-GDP ratio of around 40% well below the likes of the US (100%) and Japan (300%). These bonds are issued by the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM) with terms up to 30 years and typical buyers including banks and insurance companies, who must hold minimum amounts of capital, as well as pension funds, sovereign wealth funds and investors like clients of Wattle Partners.

The actions of the Reserve Bank outlined above, of purchasing government bonds and pushing yields down to 0.25%, effectively increases the attractiveness of newly issued bonds and ensures that they remain in high demand. In fact, the AOFM delivered its largest bond auction in history in April, raising $13 billion, but receiving over $200 billion in bids. The split of buyers, shown above, was enlightening.

This report was written by Jamie Nemtsas, Financial Adviser and Director of Wattle Partners.

[ls_content_block id=”19823″ para=”paragraphs”]