What a month (or three) it has been for ASX investors. Record highs, the fastest falls on record, unbelievable capital raisings, social distancing and lockdowns and back again.

Investors are scrambling to find some direction in the market.

Bank stocks

Last weekend, I was fortunate to go live on Sky News’ Business Weekend with Ticky Fullerton to chat about Commonwealth Bank’s (ASX: CBA) third-quarter report, Westpac’s (ASX: WBC) possible multi-trillion-dollar AUSTRAC fine, Caltex’s rebranding to Ampol and the trade war with China.

As is usually the case, before I sit down to record an interview, podcast or report, I go back over the source material just to check I’ve got my facts straight — and don’t make a fool of myself on live telly!

The first cab off the rank, so to speak, were the Big Banks…

(Note: the last time I sent an email about ASX bank stocks to Rask readers I got a feisty email in reply which read: “…you should be reported to the authorities…” Poor fella.)

As reported on Rask Media, Commbank delivered its results showing a good underlying profit but a whopping $1.5 billion in provisions for expected credit losses and remediation.

On a more positive note, while 240,000 mortgage repayments were put on hold, I was optimistic about the bank after seeing its modelling of risk exposures, capital buffers and its funding position.

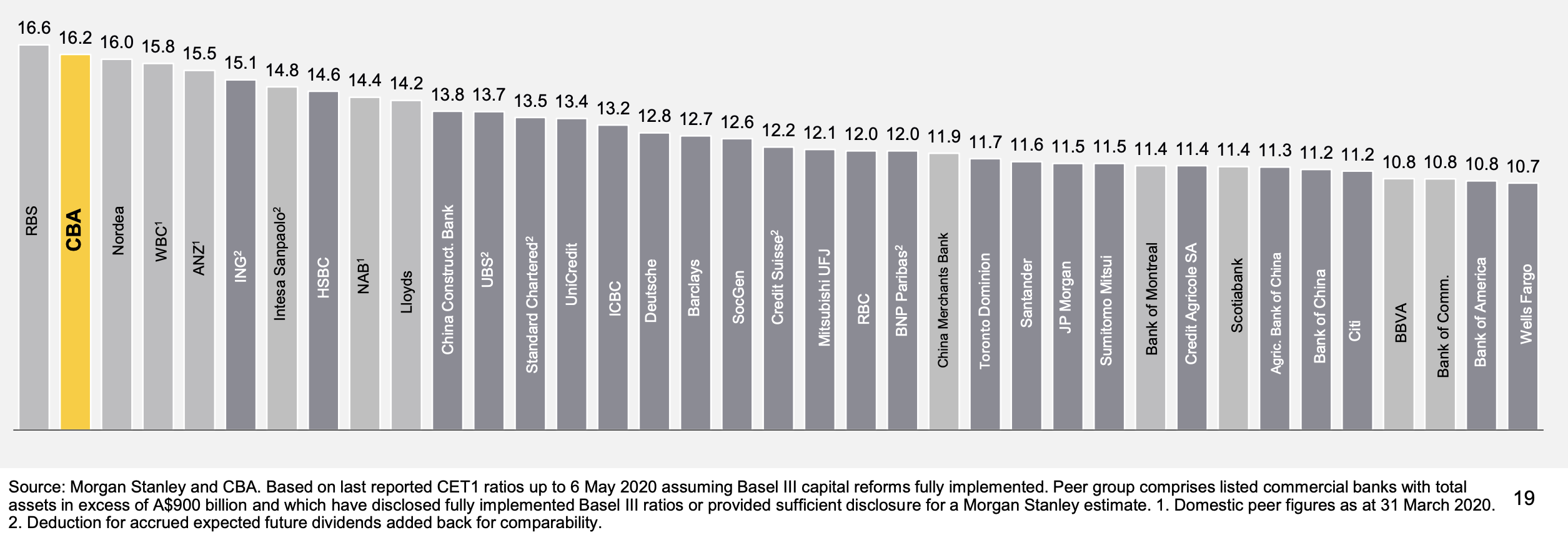

As you can see in the following chart, CBA is, by international standards, amongst the highest-rated banks in terms of its protective capital buffer (known as CET1).

The capital buffer does not guarantee dividends will be paid but it’s a reassuring sign of the bank’s policy towards funding (note NAB’s position in the list).

Other things which jumped out to me in the third-quarter report were the increase in customer term deposit funding of loans, which stood at 70% of loans as of March 2020 versus 55% during the GFC; and the longer-dated maturity of its wholesale funding, which sat at an average 5.3 years in March 2020 versus just 3.5 years during the GFC.

Westpac’s horrible risk culture

I’m less positive about the prospects for Westpac shares after it announced a $2.2 billion impairment charge. In my opinion, Westpac has proven again why it’s probably the least ethical of all the major banks and its risk culture must change.

The bank is facing the same headaches caused by COVID-19. However, Westpac shareholders are still digesting the news that AUSTRAC said the bank failed to adhere to money laundering rules, and the allegations it failed to identify payments which may have been used to facilitate child exploitation.

With all of the banks moving away from wealth management, investors should be valuing their banks based on the net interest margins — the profits made by banks from lending money.

Negative interest rates

The elephant in the room for investors and policymakers alike is negative interest rates. It’s even been tossed around as a good idea by none other than US President Donald Trump in a Twitter storm.

Negative interest rates come about when the demand for ‘safe haven’ assets like Government bonds push the price of a bond up to the point where the yield (i.e. the expected return) is negative. If an investor bought $100 of that bond, they would be guaranteed to have less than $100 when the bond matured.

The reason so many investors buy bonds, even if they’re negative, is because they believe Government-backed bonds are the safest place to park their cash. Unfortunately, negative interest rates are not nearly as glamorous as they seem. For example, you won’t be getting paid to have a credit card!

For banks, negative or low interest rates can create a few headaches. Indeed, despite reporting record profits in dollar terms, Australia’s major banks have actually become less and less profitable, per dollar lent to customers, over the past 10 years. Their margins have been squeezed because the difference between the cost to acquire funds (e.g. customer term deposits) and what the bank collects (e.g. mortgage repayments) has been getting narrower.

Caltex

A blast from the past.

Caltex is rebranding as Ampol while also temporarily shutting its Lytton refinery — one of only four refineries in Australia — after seriously low oil prices sandwiched its profit margins.

As I said on Sky, Caltex’s management is grappling with lower oil prices, a brand name swap, an alliance with Woolworths and management change.

That said, there’s a chance that when the company emerges it may be on a stronger footing (i.e. in two-to-three years) once all is said and done… provided it doesn’t get another takeover offer.

If you ask me, Caltex management has made it very clear they’re still for sale.

Note: we don’t own Caltex/Ampol shares inside Rask Invest, but it’s a very interesting company.

Trade wars

Right now, another sector facing some extra pain is the agricultural industry, although you wouldn’t know it if you read through Graincorp’s (ASX: GNC) recent results.

With China slapping a massive trade tariff on Australian barley imports, a commodity used by them to make beer and feed animals, Aussie grain farmers will be feeling the pinch. This comes after years of drought and swine fever impacted farmers.

Again, Rask Invest’s share ideas are not exposed to the agricultural sector.

In my experience agriculture is a hard market for farmers. However, it could even harder for ASX investors.

Why?

Ask any farmer with a great patch of dirt how they got it and chances are they will tell you that the property has been “in the family for generations”.

My point is that the best assets in agriculture rarely make their way onto the stock market because they are usually gobbled up by big farmers, trusts or international investors. So between that challenge and the issue of most farms having no competitive advantage, it’s an industry I tend to avoid when we’re going on the hunt for multi-baggers.

Where to from here

No-one knows for sure what comes next for markets, in the short-run (less than three years), or in the long run (three years or more).

However, the good news is that the best investment advice rarely changes:

Find great companies, led by great management, with leading products and exceptional growth runways, then invest regularly. Forget the rest.

As one famous Wall St Journal columnist says, a good journalist is paid a wage to say the same thing 250 different ways each year.

My job — and passion — is finding great Australian and global companies that Rask Invest members can buy and hold — ideally — for decades. Negative interest rates or not.

[ls_content_block id=”14945″ para=”paragraphs”]