It’s a Sunday evening, a glass of red in hand, and I was watching Oaktree’s Howard Marks opine on markets, crypto, fed policy and distressed investing with Bloomberg’s Romaine Bostik (fantastic interviewer). While his points were not novel, I was dumbstruck by the implications of Marks’ comments.

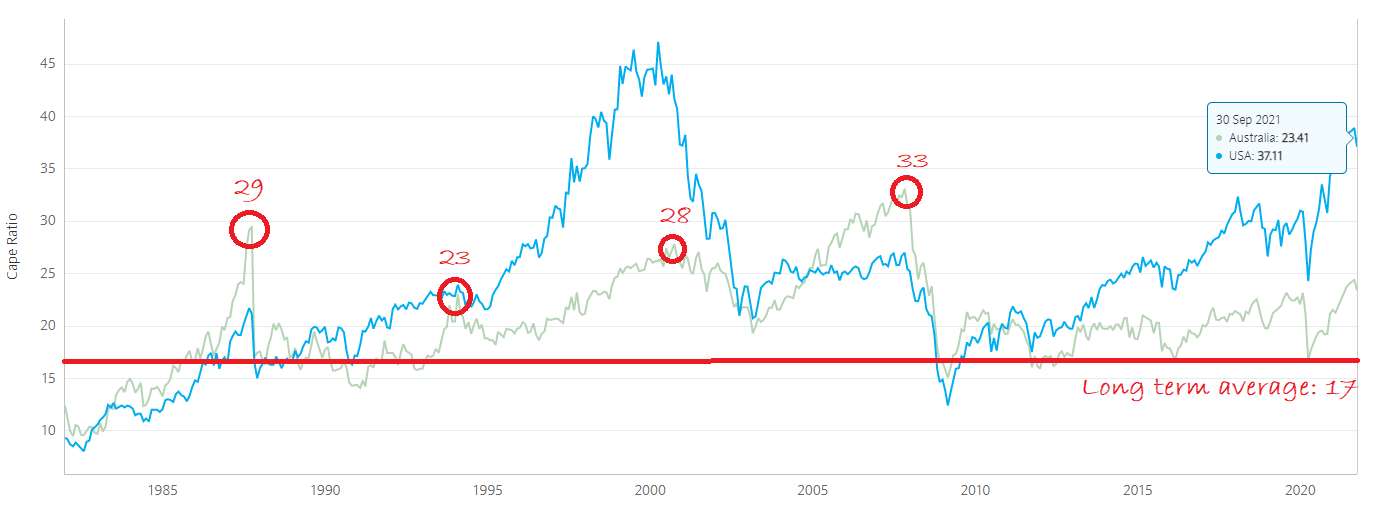

Marks noted that due to high valuations in the current markets, forward returns are going to be lower. Thus, investors seeking moderate returns are being pushed into riskier assets such as emerging markets, private equity, and cryptocurrency. Reflecting on the ASX, I wondered are we value investors inadvertently being pushed towards value traps?

What is a value trap?

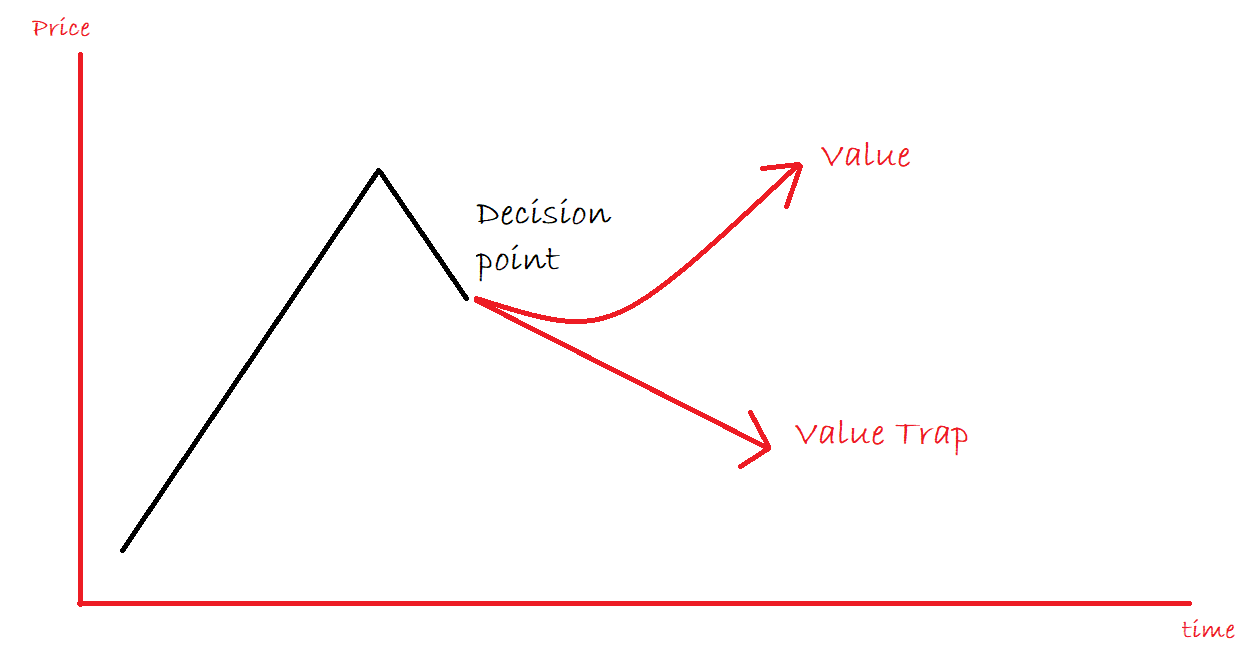

Value traps are companies that are trading at such low valuations they appear to be a bargain. Low valuations may be based on price to earnings, enterprise value to free cash flow, net tangible assets per share, etc. Typically, they relate to price or asset-based valuations, and are historical not forward-looking.

While being cheap is a necessary condition, it is not sufficient for a ‘value trap’ – it must also consistently underperform in terms of growth. This may become apparent through declining earnings per share, declining free cash flow, reduced dividends, increased dividend payout ratios, and or declining net tangible assets per share.

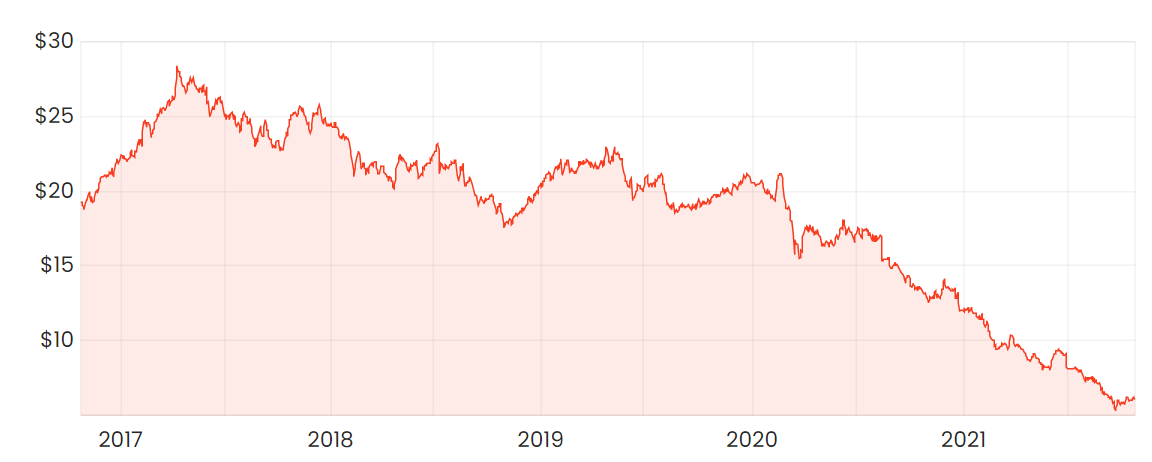

AGL (ASX: AGL) has been a typical example of a value trap. Ever since government policy has put downward pressure on household energy prices, it’s caused the cost of capital to exceed its potential returns. Yet, it continues to trade on historical low multiples, pays apparently a high dividend, while earnings continue to falter.

AGL share price

Source: Rask Media AGL – 5 year share price

It’s hard to differentiate value from a value trap

Value investing typically involves buying businesses at prices below their intrinsic value. It’s understood that due to the psychology of the market, share prices often overshoot: when the market is overly bearish on a company, they become overly cheap; similarly when the market is overly bullish on a company, they can temporarily become overpriced.

Value investors may have an edge by understanding this psychology and leaning against it. This may express itself as being more optimistic on future growth rates. However, if their optimism is misplaced, then they may have fallen victim to the value trap. This is particularly bad if this crosses the threshold into ‘shrinking company’ space – while it’s not great if you buy 25% growth but only get 15%, it’s much worse if you buy 5% growth and get a 5% decline.

Trapped in the ASX’s prisoners dilemma

The ASX has some high-quality businesses. However, as money flows to these few businesses their valuations become increasingly stretched. CSL

(ASX: CSL) is a great Australian company, though at multiples of ~45x earnings with forecast growth of ~13% CAGR, it’s not cheap. Finding growth at a reasonable price seems to have become nigh on impossible.

In contrast, we are flush with examples of businesses that once were quality and now are in the doldrums. A2 Milk (ASX: A2M) has fallen from grace with Covid impacting on the daigou channel; Magellan Financial Group (ASX: MFG) has underperformed its peers over the past year and funds under management have stagnated; Appen (ASX: APX) faced delays from its major clients (i.e. Facebook, Google) on advertising related global services; and Service Stream

(ASX: SSM) has lost its NBN contracts in some of the most profitable jurisdictions.

To separate the wheat from the chaff, I look for three things:

- Positive earnings growth even if low;

- Multiple products, services, and or avenues for growth; and

- Decent margin of safety

Final thoughts

As we value investors are pushed further up the risk curve, we need to be increasingly mindful of avoiding value traps. There are other options out there – but it shouldn’t require buying growth at an unreasonable price.