A little while back, I — Owen here — received a great question after we closed question time in a Rask Live session, asking ‘what are 10 reasons why an investor would sell shares (besides thesis break)?’.

Instead of answering ‘10 reasons why we would sell a stock’, we’ve gone with 10 common reasons we hear or see other investors selling.

(Editor’s note: this article first appeared a a couple of years ago, inside our old membership service. We’ve since discontinued that all members are now part of Rask Core.)

We’ve tried to provide what we believe is the common thought process and signals behind these decisions, as well as our thoughts on why or why not it might not work as a valid sell signal. Where we can, we’ve also tried to share resources that can help you explore the individual ideas more deeply.

Reason #1 – You need the money

Along with just about every other investment professional, Rask has long held a stance that the stock market, whether via individual shares, ETFs or funds; is no place to park money that may be needed within a 2-3 year time horizon. For example, I wouldn’t invest in a fund like Lakehouse Capital or an ETF like Vanguard Diversified High Growth Index ETF (ASX: VDHG) if I knew I might need that money in 2 years. I wouldn’t invest in shares of Alphabet Inc Class A (NASDAQ: GOOGL) if there was a chance I’d need it in three years.

The reason is pretty simple: the stock market is volatile. EML Payments Ltd (ASX: EML) shares fell 45% last month, in a single day, before the market quickly realised it probably wasn’t that bad. Imagine having $10,000 invested in EML and you needed to fund, say, a holiday, new car or hospital visit — and you were forced to sell on that day.

The reason we take this view with invested capital is much the same when we avoid debt in our investing, and the reason we like companies without debt: you never want to be a forced seller.

“When major declines occur, they offer extraordinary opportunities to those who are not handicapped by debt” –Warren Buffett

Still, all this said, sometimes there are unexpected things that pop up. Terminal illness; severe, expensive and prolonged hospital visits; divorce; changes in short-term goals (e.g. a child needs to go to a particular private school).

The best thing to protect your portfolio from these events actually has nothing to do with your portfolio at all:

- Have 6+ months of emergency cash set aside (or 2-3 years’ worth if you’re nearing or in retirement). These funds aren’t part of your investment portfolio.

- Get reliable income protection (you might opt for cover to 65 years of age, to kick in after a waiting period of 6 months)

- Ensure you, your family and business partners have adequate life/death and other insurances (and a will!)

At the very least, these strategies should buy you time and allow you to focus your selling decisions on other, more logical reasons to exit a position.

Reason #2 – Valuation: the company has shot up past its intrinsic value

This one is pretty obvious, often talked about… and it’s probably a mistake to focus on this too much.

We’ve covered valuation theory at length, especially in our free share valuation course and highly regarded Value Investor Program.

Basically, investors and analysts (like us) use models — such as Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis — to determine the ‘fair price’ of a company. We then compare the intrinsic value (IV) to the stock price of the company. This video explains the basics:

I’ll play a straight bat with this one: it’d be a mistake to sell companies based solely on things like ratios (PE ratios), dividend yield, or other simple factors. As long-term investors, you/we need to be smarter than that. At the very least, if you’re relying on valuation playing a big part in your investment strategy, you should use a DCF.

There are a few things you should know:

- Valuation is at least as much art (“thumb-sucking”) as it is science

- In my view, ‘generally correct’ is far better than ‘specifically wrong’ because even if your valuation is looking fly, there’s no guarantee the market will bid up the stock price to make it useful

- Fund managers, analysts and other commentators use valuation as an out. “We exited our position due to valuation” [translation: 50% of the time it’s another reason] or “the valuation doesn’t look right” [they probably don’t know what a good valuation is]. Experts also like to quote valuation because it’s jargon-rich and as such, it easily confuses most audiences and positions themselves as experts who know something your average investor doesn’t.

If you want to understand the limitations of valuation in practice, jump onto Twitter and follow a few short sellers. They’ll be outraged, often: “clearly the company is overvalued” or “can’t everyone else see this, it’s cheap!”.

If you’re a long-time listener of The Australian Investors Podcast (thanks!), you’ll realise that when I have short sellers on the show they often say “we don’t short on valuation alone”. Translation: there are zero guarantees the market will agree with your valuation anytime soon.

“In the short-run, the stock market is a voting machine. Yet, in the long-run, it is a weighing machine.” – Ben Graham

Reason #3 – The company is being acquired

If you’re in the stock market for long enough, eventually, you will find that a company you own or follow gets acquired.

However, if you invest in very high-quality companies (and you’re doing your valuation work) this will happen more often than you’d like. You see, many investors rejoice when their company is the subject of a takeover proposal — usually because the shares leap higher on the news.

Personally, I find the news that your company is getting acquired to be a bit frustrating, especially here in Australia where most good small and mid-cap companies are taken over before you can truly benefit from owning the stock. Australia tends to be a very fruitful hunting ground for much larger US, European and Asian companies.

There are worse things than being a forced seller during a takeover. That said, it must be a fair and reasonable price. Depending on the offer, I often sell my shares before an acquisition takes place and move on.

Reason #4 – Opportunity cost: you think you can get a better return elsewhere

Similar to the commentary on valuation above, there’s a cost with everything we do. By choosing to hold EML Payments shares at a full value, we might be giving up the opportunity to buy Xero Limited (ASX: XRO) shares when they’re cheap, or vice versa.

Hamish Douglass, the renowned fund manager from Magellan Financial Group (ASX: MFG); and Chris Judd, the former AFL superstar turn private investor; both told me they think of their portfolio as a sports team, with substitutes on the bench (i.e. your watchlist) waiting for a spot on the field.

For a fund manager like Hamish, I think this is a neat analogy. But keep in mind a fund manager like Hamish does not always take into account the taxes paid on buying and selling shares. Indeed, a unit trust structure — which is what most funds are made of — sees the tax events caused by the portfolio manager (e.g. Hamish) ‘pass through’ to the investors (like you).

This is a big gripe I hold with funds management reporting, especially when we consider the average fund manager has very high portfolio turnover and an average holding period of 7.4 months.

Thanks, @Magyer. That accords with what I've always said about the market, which is that it's pretty efficient in the near term but that its fatal flaw is that it prices "two quarters out." Just play a longer game than that & you're fishing in a small, stocked pond. Great find!

— David Gardner (@DavidGFool) May 21, 2021

Okay, back to the topic.

Selling a share because you find a better idea is one of the finest reasons I can think of to exit a position. However, it’s not always clear cut and you must make sure you find a new opportunity that outweighs the tax and fees involved in selling.

Keep a journal of your trade decisions because I’ve found a lot of new investors (i.e. those with less than 5 years’ experience) find themselves selling for this reason more often than they’d care to admit. After five years, the best new investors I come across can count the number of shares they’ve sold on one hand.

“I could improve your ultimate financial welfare by giving you a ticket with only 20 slots in it so that you had 20 punches—representing all the investments that you got to make in a lifetime. And once you’d punched through the card, you couldn’t make any more investments at all… Under those rules, you’d really think carefully about what you did and you’d be forced to load up on what you’d really thought about. So you’d do so much better.” – Warren Buffett

Reason #5 – Tax purposes

A sale for tax purposes can happen, but it’s often not the best idea to sell shares, ETFs (or any investment) for the explicit purpose of ‘tax loss selling’ as it can attract harsh penalties from the ATO.

For example, some investors sell shares in the month of June to buy again in July. Just be careful to ensure the ATO cannot prove the sole reason for selling was to reduce your tax bill.

This blog post from SelfWealth explains the process in more detail.

Reason #6 – Temporary shocks/headwinds

Macroeconomic conditions, such as COVID or the Global Financial Crisis, changes things. One minute you’re forecasting 10-20% top-line growth for your company over the next 5 years, the next minute you’re asking ‘can it survive?’.

All Rask analysts, and nearly every investor I follow, is ‘bottom-up’ (most of the time). ‘Bottom-up’ investing is about focusing on the business fundamentals (products and services, its sales, debt, cash, management, etc.) then moving ‘up’ to higher-level considerations like the industry, competition and market size.

A bottom-up approach is contrasted with a top-down approach which sees investors take into account the ‘big picture’ first and foremost. At the very top, we have ‘macro funds’. These types of funds only take into account big data points like inflation, interest rates, GDP, employment and trade balances. In my experience, these strategies rarely work as well as good bottom-up strategies. For me, right now, top-down strategies often involve too many complex and conflicting signals and it’s often quite difficult to find a good expression of the trade.

However, no matter which technique you use to formulate your investment strategy there is always some interplay between the macroeconomy and individual companies. For example, eventually, fast wages growth catches up with even the most resilient businesses. In early 2020, just before COVID first hit, a super-wide moat business I own, Xero Limited (ASX: XRO), was flying — adding more customers than ever, gushing free cash flow and the short, medium and long-term outlook was nothing but bright.

Less than a month later, the world was beginning to hear a contagious virus from China. Overnight, Xero’s once sunny outlook became gloomy, clouded by the likely impact of small businesses being forced to close for lockdown.

To be sure, it wasn’t that Xero was doing a poor job (it later turned out it was doing quite the opposite — customers relied on it, even more, to file for tax relief, employee benefits, and various government subsidies). The thing is, Xero was in the midst of a rapid uphill growth phase. But, like all businesses, it needed a few things to go right in the short term — namely, adding subscribers and generating more free cash flow — to underwrite its valuation and fuel future growth.

This is just one example of a macroeconomic shock potentially changing the game on bottom-up investors like us. As always, and as you probably guessed, I’d come back to this: focus on high quality, wide-moat, financially secure companies. Yes, you pay more for them. But when (not if) grey skies appear, you’ll rest assured knowing you own a company that can survive — and thrive — through difficult times.

Finally, an easy way to test if you overestimated the growth of an industry or company within it is to find industry reports, like those from Grandview, Statista (sometimes less reliable) or IBIS, to name a few. Is your company growing its annual revenue faster than the industry? That means it’s taking share (or defining its own market). Or is it slowing relative to the sector?

Keep in mind the industry reports can be unreliable and the definitions applied might not match your company. If that’s the case, benchmark your company against competitors. For more reading on why market size is important, listen to my podcast with Joe Magyer and read my notes on Why Total Addressable Markets Matter.

Reason #7 – Director/Management sell-down

Peter Lynch, famed US fund manager and author of popular investing books like One Up On Wall St, is attributed to this quote:

“…insiders might sell their shares for any number of reasons, but they buy them for only one: they think the price will rise.” – Peter Lynch

Basically, what he is saying is that ‘if the people with all of the information (company insiders) are selling, it could be time to sell because they know more about the business than we ever could.

When a company insider, like a CEO or director, sells their stock, they’re often required to report that to investors, either via an ASX release (Change of Directors Interest Notice), or via the SEC’s EDGAR website for US companies (note: this website is uglier than John Howard’s leg spinner). Alternatively, it’s easier (but a delayed signal) to read an ASX-listed company’s Annual Report or US-listed company’s Proxy Report (filed after the Annual Report / 10K).

The thing is… I believe far too many investors overweight this ‘signal’:

- Management sell = you sell

- Management buy = you buy

If you do that, I reckon you’ll be setting yourself up for failure.

One of the ways investors go wrong with this signal is they use management’s transactions as a source for confirmation bias. Of course, confirmation bias is something you can’t see — and most of us can’t control it. The best we can do is be aware of it.

Basically, confirmation bias is a trick our minds play on us to seek out confirming evidence of a prior held belief.

For example, Pro Medicus Ltd (ASX: PME) — arguably the ASX’s best company over the past 10 years — has forever been criticised as being “expensive”. Even yours truly sold some of his shares at ~$13!

To rub salt into the wound, I said: “At $13.62, none of my forecasts for profit can justify holding such a large position in the company.”

That was January 2019.

Pro Medicus co-founders Sam Hupert and Anthony Hall moved to sell some (1 million shares) of their then holding (29.1 million shares) in March 2018. Shares traded between $8 and $9 in March 2018. About 18 months later (September 2019) they sold one million shares at ~$36. In February 2021, they sold another one million shares… at $45.97.

These are the two (extremely intelligent) people who know Pro Medicus better than any analyst, insider or director in the world. You should know, I interviewed Sam Hupert not too long ago:

Bottom line: management selling is not binary. It’s not black and white. Nor is it a red alert.

At most, you can apply a traffic light system to this signal and slot it neatly into the “amber” (orange) bucket.

Meaning, it’s a chance to slow down, reflect on your thesis, position sizing and valuation — or accelerate! — but don’t let management grab the steering wheel of your portfolio because they’re not always right — and sometimes they sell for reasons outside of what’s happening within the company.

Here’s a tweet from global small-cap investor, Ian Cassel, that I found relevant in writing this:

My thoughts on insider selling changed when a stock I was in 10x in 2 years while the CEO sold 30% of his holdings. He said,"Bills, kids, a beach house, but I would never sell stock if the business wasn't crushing it. I don't need that on my conscious."

Still all about character

— Ian Cassel (@iancassel) June 6, 2021

Reason #8 – When you’ve reached your investment goal

Okay, so you’ve got $2 million, $20 million or $200 million? That sounds like a good time to settle down, take some chips off the table and get on that riverboat cruise to Cologne.

Yeah, nah.

In the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, you might have retired with $1 million, parked it all in cash (or at least the majority) and earned $150,000, $90,000 or $60,000, respectively, just from bank interest. Nowadays, even $2 million is lucky to get you $15,000!

So, the thing is: you must be invested in growth assets. Even if your split is 20% (growth) and 80% (cash), which would be very conservative indeed, you must be invested. And let’s not forget the average life expectancy is 85 for men (who were aged 65 in 2018) and 88 for women (who were aged 65 in 2018).

Of course, as the brilliant Morgan Housel once alluded to, the easiest way to feel wealthy is to raise your humility (live a more humble lifestyle) than your income. This theme in psychology, lifestyle and money is why the FIRE movement is so popular (and why our FIRE course is often #1 on our charts).

You should also know that Kate and I spoke to the brilliant Morgan Housel about these topics.

In my opinion, if you’re thinking that retirement = sell shares. Don’t. You will need to be fully invested — and it can be an extremely valuable time to start the fastest compounding of your life.

You don’t have to buy stocks or spend your days unearthing hidden growth companies. For a hands-off, income rich solution, consider using a low-cost ETF portfolio with a sprinkling of Aussie shares ETFs.

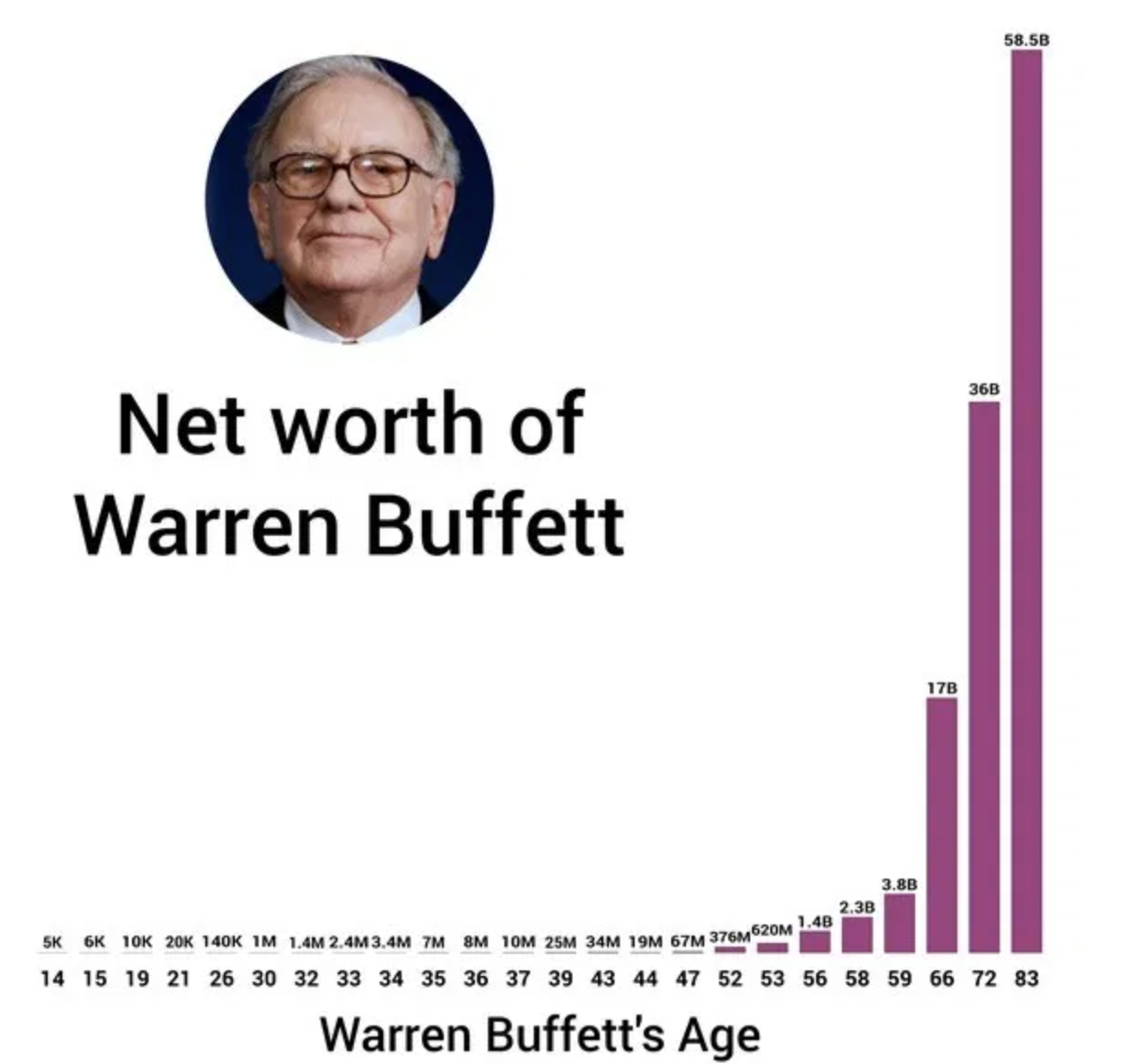

Final point: did you know Warren Buffett made 99% of his wealth after 50? As shown in the chart below he was ‘only’ worth ~$300 million at age 50. By 91 his was worth around $109 billion. That’s (109/.3) 363x times his worth when he could have retired.

Buffett didn’t work 363x harder or longer – he simply stuck to his investing and knew that his wealth would take care of itself if he managed his retirement fund prudently.

So much for selling stocks upon retirement…

Reason #9 – You need to rebalance your portfolio – either because it’s out of balance or because your investment goals change

In professional investing circles, the most common approach to portfolio construction — how you build your portfolio — is to use a technique known as Strategic Asset Allocation or ‘SAA’, together with something called Tactical Asset Allocation or ‘TAA’.

I spoke about this concept at length with my business partners and financial advisers Jamie Nemtsas and Drew Meredith, in a podcast called “Portfolio Construction Essentials“.

Here’s what you need to know about the SAA-TAA approach:

- SAA – your strategy is all about the long run. How are you going to be invested for 15 to 20 years? That’s right — this is bottom-drawer stuff. In the most basic terms, it’s about deciding how much growth (riskier) versus defensive (protective income) assets you have in your portfolio. For example, for a young person with high risk tolerance, it might be 80% growth (ASX and global shares, REITs, LICs, funds) and 20% defensive (bonds, cash, etc.). For someone in retirement, it might be 60-40. I don’t include my home (a lifestyle asset) or my emergency cash (for living expenses) in this ratio. Because this is the largest part of a portfolio, the way I think about this is: the SAA should rarely — if ever — change in a big way. Sure, you might trim positions or add new exposures (e.g. a new ETF or managed fund), but wholesale changes shouldn’t happen.

- TAA – the tactical part of your portfolio is, well, tactical. You take a small part of your portfolio (e.g. 5% – 20%) and make investments with a 2-5 year view. For example, you might think: I’m going to add an extra 10% of your overall portfolio to small-cap shares, for extra growth. You write down your reasons, determine how you’ll do it (funds, ETFs, individual shares, etc.) and execute.

Note: another way to think of SAA is the ‘core’ of your portfolio, while the TAA could also be known as the ‘satellite’, as I explain in the video below:

How does this relate to selling?

Investors use their SAA, which is often written down in an Investor Policy Statement (IPS), as their guide rails. Like a bowling ball bouncing off a bumper or a handrail up some stairs, the SAA keeps you going in the direction you want, regardless of your short-term mindset (fear, greed, envy, etc.), which often changes due to market conditions.

Good investors will use their SAA and rules contained in their Investor Policy Statement to set ‘rebalancing rules’. For example, if you want to invest 80% in growth assets like shares, but after two years you notice your portfolio mix rises to 88% in shares and 12% in defensive/income assets, you could have added a rule in your IPS to say:

- “I can rebalance whenever my portfolio is 2.5% away from my SAA”

- “I must rebalance whenever my portfolio is 5% away from my SAA”

I have found that these rules, written in advance, save investors during market crashes. They save investors from letting the pendulum of fear and greed flip their life-long wealth goals upside-down. Again, these are safety bumpers.

For example, during the crash of the GFC and again in 2020, when COVID first struck, investors jettisoned their shares and stuck extra capital into cash/savings accounts. That was the exact worse time to do it. Instead, what they should have recognised is: ‘my defensive assets have done their job, but I’m under-invested in stocks — I’ll rebalance by buying more shares’.

Had those same investors sat down to carefully think about their goals and risk tolerances, and written out their investor rules, they wouldn’t have done that. These rules help you make scary, good decisions at the time you need them most.

This reason for selling, #9 on my list, is tied for the most important reason to sell a stock or investment. It’s only second to the #10 reason investors sell shares because this is a portfolio decision rather than a company-by-company decision.

Reason #10 – Thesis break

Last, and certainly the most important is thesis break: the only real reason I sell shares in a company.

A thesis is your reason for making an investment and owning it. This, obviously, must be formulated before buying into an investment.

There is an easy way to explain what a thesis is and how to know if it’s broken. Just ask yourself a question:

Why do I own the stock?

When a friend asks you, “why do you own that investment?”, what is your response?

“PayPal is the world leader in payment gateways and payment apps. It makes it super-easy and secure to buy stuff online, sell things you don’t need and transfer money to people. It’s becoming more and more popular.”

Humans tell ourselves stories to help us break down complex ideas, and these can lead investors astray. However, the important takeaway from the above is that by saying those few sentences, you have identified the ‘essence’/value proposition/central question of why the company exists; and you have determined why you own it (it’s becoming more popular).

If the narrative changes in one year from today, for example, when prompted you say: “More people are using Apple Pay instead of PayPal these days”, your thesis might have been broken.

The problem is narrative bias kept bottled in our heads can be a fair-weather friend.

If you do not write down your thesis it will be easily forgotten or twisted to fit a changing circumstance — you will never truly know if your thesis is broken.

There is a reason the best investors to have ever lived — Ben Graham, Warren Buffett, Charlie Munger, Peter Lynch, Howard Marks, etc. — are brilliant writers. It’s not because they love the subtle tremble of a ballpoint pen across paper. It’s because it must be done.

To think, and invest, clearly, you must formulate your thesis and write it down. This thesis is your current self protecting your future self.

A thesis is your repellent to the monkey brain. A peg when your brain farts.

A thesis is formed from your intellectual hard work. Hard work is what few investors do (including most professionals). It’s what defines great investors from great analysts, great investors from the mediocre.

Of course, this hard work is why Rask exists. We do the work and write down our thesis for every investment, so you don’t have to. Over the next 10-20 years, we believe this will guide us, and our members, down the pathway towards lifelong wealth.

***

Please note: this article first appeared a a couple of years ago, inside our old membership service. We’ve since discontinued that all members are now part of Rask Core.

Thanks for reading!